Private vs. Federal Loans: The Choice Students Didn’t Know They Made

Most students don’t remember choosing between private and federal loans.

They remember choosing a school.

They remember an acceptance letter, a campus tour, a counselor saying, “Don’t worry, we’ll help you figure out the financing.” They remember clicking through portals, signing forms, watching numbers appear and disappear on a screen. It all felt administrative, procedural—something you had to do to move forward.

And yet, hidden inside that paperwork was one of the most consequential financial decisions of their lives.

Not whether to borrow.

But how.

The Decision That Didn’t Feel Like a Decision

In theory, the difference between federal and private student loans is clear. One is backed by the government, comes with standardized protections, and is designed—at least on paper—to balance access with affordability. The other is offered by banks and lenders, shaped by profit incentives, and governed by contracts that look more like credit cards than public policy.

In practice, however, many students never experience this as a choice.

The language is technical. The timing is rushed. The context is emotional. You’re not sitting down to compare loan terms the way you would compare mortgages or car loans. You’re trying to secure your place in a future that’s already been framed as non-negotiable: college equals success.

When money becomes the last obstacle standing between you and that future, the form of the money matters less than the fact that it exists.

That’s how the choice disappears.

Federal Loans: The Baseline Students Rarely Understand

Federal student loans are often described as the “safer” option—and compared to private loans, they usually are. But safer doesn’t mean simple, and simple doesn’t mean fully explained.

Federal loans come with fixed interest rates, income-driven repayment options, deferment and forbearance protections, and, in some cases, forgiveness programs. These features are supposed to act as shock absorbers when life doesn’t go as planned.

The problem is that most students don’t learn about these protections before they borrow. They learn about them years later, often while scrambling to manage payments.

At the borrowing stage, federal loans are presented as just another line item in a financial aid package. Subsidized. Unsubsidized. PLUS. The distinctions blur. What matters is the total amount covered and the gap that remains.

And there is almost always a gap.

Where Private Loans Enter Quietly

Private loans rarely arrive with fanfare. They slip in through necessity.

Tuition covered—but not housing.

Aid approved—but not enough for books, fees, or transportation.

Federal loan limits reached—but enrollment still incomplete.

That’s when private lenders appear, often recommended indirectly through school portals, comparison tools, or financial aid offices that frame them as “options.” Sometimes the suggestion is explicit. Sometimes it’s implied. Either way, the message is consistent: this is how students make it work.

The framing is crucial. Private loans are rarely described as fundamentally different. They’re described as supplemental, temporary, manageable. Just another step toward staying enrolled.

What’s missing from that conversation is the long-term cost of crossing that line.

Two Systems, Two Philosophies

Federal loans are imperfect, but they are rooted in policy goals: expanding access to education, distributing risk across society, and offering relief when borrowers face hardship.

Private loans are rooted in contracts.

They assess risk individually. They price borrowers based on creditworthiness—or more often, their co-signer’s. They are not obligated to offer flexible repayment options, forgiveness, or income-based adjustments. Their responsibility ends at the terms of the agreement.

That difference matters most after graduation, when optimism meets reality.

But by then, the choice has already been made.

The Co-Signer Trap

One of the most overlooked aspects of private student loans is the role of the co-signer. Parents, relatives, or guardians often step in, believing they’re helping temporarily. The assumption is that once the student graduates and finds work, responsibility will shift cleanly.

That’s not how it usually works.

Private lenders structure co-signer agreements to maximize security, not flexibility. Release clauses are strict. Requirements are opaque. One missed payment can reset the clock. And when borrowers struggle—as many do in early career years—the co-signer becomes financially entangled in ways they never anticipated.

This shared liability creates pressure, guilt, and silence. Students avoid discussing difficulties. Families absorb costs quietly. What was meant to be support becomes a source of long-term strain.

Federal loans don’t require this dynamic. Private loans depend on it.

Interest: The Slow Reveal

Interest behaves differently depending on the loan—and the difference compounds over time.

Federal loans have fixed rates set annually by policy. Private loans often come with variable rates tied to market benchmarks. What looks competitive at signing can become punishing later, especially during economic shifts.

But again, this isn’t obvious at the start.

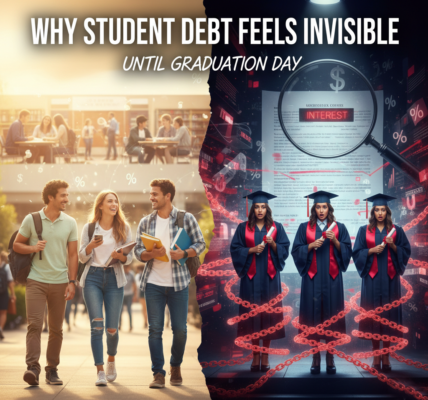

During school, payments are deferred or minimal. Statements go unread. Balances feel theoretical. The interest accrues quietly, invisibly, while students focus on surviving semesters.

Graduation is when the math catches up.

Borrowers discover that private loan payments are higher, less negotiable, and far less forgiving than their federal counterparts. There is no income-driven safety net. No automatic hardship relief. No political debate about cancellation.

Just a contract.

When Things Go Wrong

The true difference between private and federal loans reveals itself not when things go right—but when they don’t.

A delayed job offer.

A health issue.

A degree that didn’t translate into employment.

A recession that shrinks opportunities overnight.

Federal loans offer mechanisms—however flawed—to absorb some of that shock. Payments can be reduced based on income. Timelines can stretch. Forgiveness, while limited, exists.

Private loans offer none of this by default.

Borrowers can request temporary forbearance, but approval is discretionary and often short-lived. Interest continues to accrue. Missed payments trigger penalties quickly. Default escalates faster.

And unlike federal loans, private lenders can and do pursue aggressive collections.

The Myth of “Responsibility”

Private loans are often framed as a test of personal responsibility. You signed the contract. You should have known better. You chose this.

But responsibility without transparency isn’t responsibility—it’s exposure.

Most borrowers were teenagers or young adults navigating an unfamiliar system under pressure. They were encouraged to prioritize enrollment over comprehension. They were not given side-by-side comparisons that translated long-term consequences into plain language.

Calling that an informed choice stretches the meaning of the word.

Schools as Silent Intermediaries

Colleges and universities occupy an uncomfortable position in this story. They don’t issue private loans, but they benefit from them. When federal aid falls short, private borrowing keeps students enrolled and tuition revenue flowing.

That creates a quiet alignment of incentives.

Few schools actively discourage private loans. Fewer still highlight their risks with urgency. Financial aid offices often operate as neutral messengers, presenting options without judgment—even when one option clearly carries greater long-term harm.

Neutrality, in this context, favors the status quo.

Life After Graduation: Diverging Paths

Graduates with only federal loans often struggle—but they struggle within a system designed to keep them paying without collapsing. Their debt shapes their choices, but it bends when pressure increases.

Graduates with private loans experience something sharper.

Payments are fixed and inflexible. Career risks feel amplified. Entrepreneurship, public service, and lower-paying fields become luxuries. The margin for error shrinks dramatically.

Two students can borrow the same amount and graduate the same year—and experience entirely different financial lives based on a distinction they barely remember making.

Why This Choice Stayed Invisible

The private vs. federal divide stayed invisible because visibility would disrupt behavior.

If students fully understood that private loans lack forgiveness, income-based repayment, and public accountability, many would hesitate. They would reconsider schools. They would question pricing. They would demand alternatives.

The system doesn’t benefit from that pause.

So instead, private loans are framed as normal. Necessary. Just another tool. The distinction is buried under urgency, optimism, and paperwork.

What an Honest System Would Look Like

An honest system would force the comparison upfront.

It would show students how payments differ under realistic income scenarios. It would require clear warnings—not legal disclaimers—about the consequences of private borrowing. It would make federal options the default and private loans the exception.

It would treat this decision with the gravity it deserves.

Because it isn’t just about financing school. It’s about financing the decades that follow.

The Question Students Deserve to Ask—Earlier

Private vs. federal loans isn’t a technical distinction. It’s a philosophical one.

Do we treat education as a shared investment with collective risk?

Or as a private transaction where consequences fall entirely on individuals?

Most students never realized they were answering that question at 18 or 19 years old.

They just wanted to stay enrolled.

And that’s the tragedy at the heart of student lending:

the most important choice was the one that didn’t feel like a choice at all.