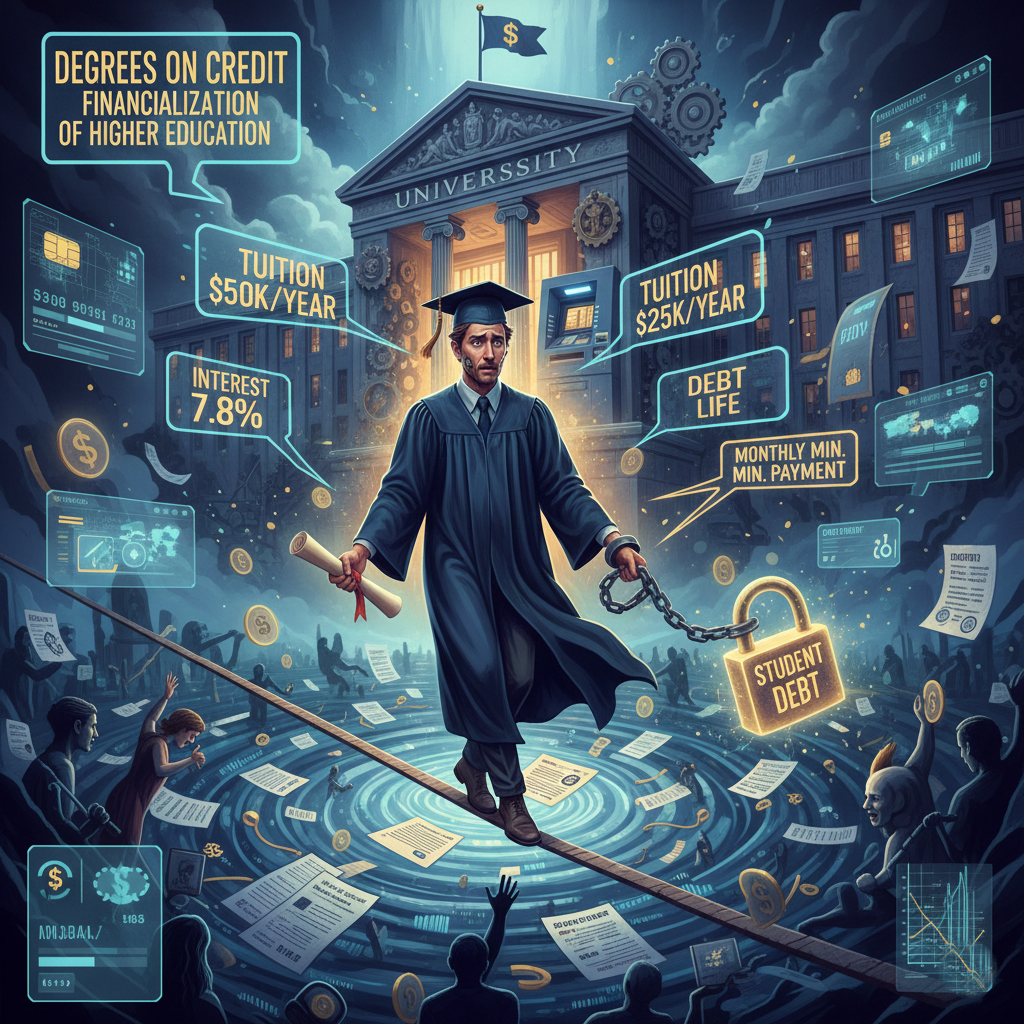

Degrees on Credit: The Financialization of Higher Education

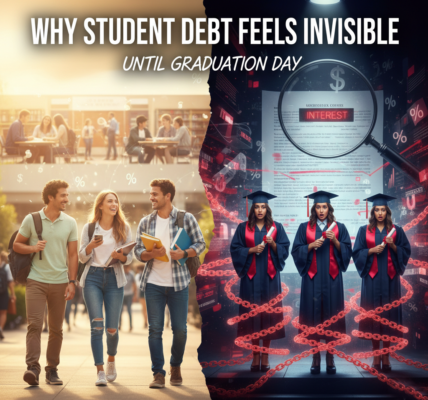

On graduation day, the caps fly into the air. Cameras flash. Parents smile. But for millions of students, the real weight of higher education doesn’t sit on their shoulders in the form of a diploma—it sits quietly in a loan account, accumulating interest.

Higher education, once framed as a public good and a ladder of social mobility, has increasingly become something else entirely: a financial product.

From Campus to Balance Sheet

Universities today look less like ivory towers and more like complex financial institutions. Tuition is priced not according to instructional cost, but according to what students can borrow. Degree programs are packaged, marketed, and financed in ways that mirror mortgages or credit cards—long-term obligations justified by the promise of future earnings.

In this system, students are no longer just learners. They are debtors.

Student loans are securitized, traded, and managed as assets. Risk is carefully calculated, default rates modeled, repayment plans engineered. The student’s life—career choices, family plans, even mental health—becomes part of a financial equation.

Education as an Investment Narrative

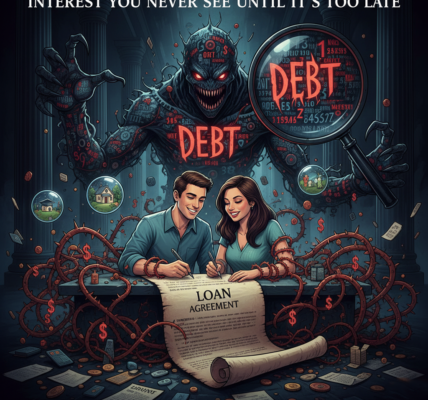

The dominant story is seductive: Take on debt now, earn more later.

Education is sold as “human capital,” a personal investment expected to yield returns over decades. If the returns fall short, the failure is individualized. The graduate chose the wrong major. Entered the wrong job market. Didn’t “optimize” their degree.

Lost in this narrative is the reality that markets fluctuate, wages stagnate, and not all valuable work is well paid. Teachers, social workers, researchers, artists—many essential professions generate social value without generating high salaries. Yet the debt remains indifferent to purpose or passion.

The Silent Shift of Risk

What makes the financialization of higher education especially striking is how risk has shifted.

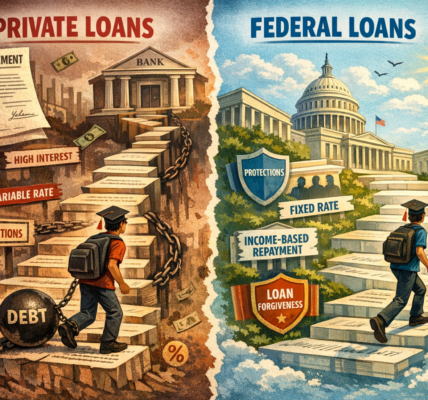

Institutions collect tuition upfront. Lenders are often protected by government guarantees. Investors earn steady returns. The student alone carries the downside risk—unemployment, illness, economic downturns, or systemic inequality.

Unlike most consumer debt, student loans are notoriously difficult to escape. They follow borrowers across borders, across decades, across life stages. A degree earned at twenty can shape financial freedom at fifty.

Inequality, Compounded

Financialization doesn’t affect everyone equally. Students from wealthier backgrounds use credit strategically; students from poorer backgrounds rely on it for access. The result is a stratified system where the same credential produces radically different life outcomes.

For some, higher education amplifies opportunity. For others, it locks inequality into place—turning aspiration into obligation.

What Gets Lost When Education Becomes Debt

When degrees are financed like assets, subtle shifts follow:

- Students choose “safe” majors over meaningful ones.

- Universities prioritize marketable programs over critical inquiry.

- Learning becomes transactional: What am I getting for my money?

Education’s deeper purposes—citizenship, curiosity, social responsibility—are harder to quantify, and therefore easier to sideline.

Rethinking the Price of a Future

The question is no longer whether higher education is worth it. The question is: worth it for whom, and under what financial conditions?

As degrees continue to be purchased on credit, society must confront an uncomfortable truth. We have built a system where hope is financed, risk is privatized, and education is measured not by enlightenment, but by repayment schedules.

And in that system, the most expensive lesson may not be what students learn in class—but what they learn about debt, power, and the price of believing in a better future.